Integers

Categories: data structures

Integers, Python type int, represent whole numbers. Most popular languages, for example, JavaScript, Java, C#, C/C++, support the int type. Python support for integers is broadly similar to other languages.

There is one important difference. Most languages store integers in a format that occupies a fixed number of bytes, which in turn means that they can only work with integers up to a fixed maximum size. For example, if a language uses 8 bytes to store integers, then integers must be in the range of approximately ±9e18. That is a very big number, 9 followed by 18 zeros. However, if an integer ever exceeds that value, it will most likely cause a program error or exception.

Python allows for integers of virtually any size. We will look at that in more detail below.

The other main type of number Python supports is floating point numbers (float) which can represent non-integer numbers such as 0.5 or 3.141592653589793.

Assigning an integer value to a variable

This code sets a, b, and c to different integer values:

a = -2

b = 1_000_000

c = 10**1000

The first line sets the variable a to -2, as you would expect. This is how many programming languages work.

The next line sets the variable b to one million. Notice that we have used underscores to split the number into units, thousands and millions: 1_000_000. The underscores are entirely optional, they are just there to make the number easier to read. It can be very useful when you are declaring large numbers.

We could, of course, have simply written the number as 1000000. Python completely ignores the underscores when they appear as part of an integer or float value. Python doesn't check where the underscores are, so if we wrote it as 100_0000, Python would still recognise it as a million. But, of course, that would be very confusing to anyone reading the code, so it isn't recommended.

Next, we set c equal to 10 to the power 1000. That is an absolutely huge number, it is a one followed by a thousand zeros. But notice that Python is quite happy with that. As we noted earlier, Python allows you to use integers of virtually any size.

The ultimate limit on the size of an integer is the amount of memory in your computer. However, calculations using an extremely large number of digits can be very slow. But Python can handle integers with thousands of digits without any serious performance problems.

Arithmetic operations on ints

If we add, subtract, or multiply two integers, the result will always be an integer:

a = 3 + 4 # Additions, gives 7

b = 3 - 4 # Subtraction, gives -1

c = 3 * 4 # Multiplication, gives 12

If we divide one integer by another, the result will always be a floating-point number. That is true even if the two numbers divide exactly:

a = 5 / 2 # 2.5 (float)

b = 4 / 2 # 2.0 (float)

The reason Python returns a float is that an integer divided by an integer might not be an integer (in the example, 5 / 2 is 2.5), so it has to be represented as a float. For consistency, integer division always returns a float in all cases, even if the value is an exact integer

If we want to handle integer division without converting to floats, we can use //, called floor division, to divide integers to give an integer result. Floor division returns the result of the division rounded down to the nearest integer:

a = 5 // 2 # 2 (int) because 5 / 2 is 2.5, which rounds down to 2

b = 12 // 3 # 4 (int) because 12 / 3 is 4.0, which rounds down to 4

c = (-5) // 2 # -3 (int) because (-5) / 2 is -2.5, which rounds down to -3

Notice that a is 2, but c is -3, because floored division always rounds down.

The operator %, called modulus, returns the remainder when two integers are divided. Here are some examples of modulus:

c = 5 % 2 # 1 (int) because 5 / 2 is 2 remainder 1

d = 12 % 3 # 0 (int) because 12 / 3 is 4 remainder 0

The operator ** raises a number to a power. For example, 3 ** 2 calculates 3 squared, which is 9. Here are some more examples:

a = 2 ** 3 # 8 (int) because 2 cubed is 8

b = 4 ** -1 # 0.25 (float) because 4**-1 is 1/4

c = 2 ** 0.5 # 1.4142135623730951 (float) because 2**0.5 is the square root of 2

In the first case, we are raising an integer to a non-negative integer power, so the result is an integer.

In the second case, we are raising an integer to a negative integer power. A negative power implies a division, for example, 4 to the power -1 is 1 divided by 4. Since division is involved, the result is always a floating-point number.

In the final example, we are raising an integer to a fractional power. This calculates a root, for example, 2 to the power 0.5 calculates the square root of 2. This always gives a float result.

In summary, an int raised to a non-negative int power gives an int result. An int raised to any other power gives a float result.

Integer conversions

There are several useful functions for converting between integers and other types.

str can be used to convert an integer value to a string. For example:

a = 321

s = str(a) # s will contain string value "321"

It is also possible to convert an integer to a string using a different number base. We can do that using the format function. This function takes a format specifier that can be used to convert the number to a string using binary (base 2), octal (base 8) or hexadecimal (base 16):

a = 123 # Decimal number 123

s = "{0:b}".format(a) # 1111011 (321 in binary)

s = "{0:o}".format(a) # 173 (321 in octal)

s = "{0:x}".format(a) # 7b (321 in hex)

s = "{0:X}".format(a) # 7B (321 in hex)

Notice that x and X both perform a conversion to hexadecimal. x uses lower case letters (eg 7b), X uses upper case letters (eg 7B).

The int function can convert different values to integers. We can convert a floating-point number like this:

a = int(2.7) # rounds to 2

b = int(-2.7) # rounds to -2

A floating point number is rounded to create an integer. Numbers are always rounded towards zero, so positive numbers are rounded down (2.7 rounds to 2), and negative numbers are rounded up (-2.7 rounds to -2).

If you want to round differently, you can use the following functions. You will need to import math to use these functions:

a = math.ceil(2.7) # always rounds up (gives 3 in this case)

b = math.floor(2.7) # always rounds down (gives 2 in this case)

Notice that the floor function used the same rounding method as the floor divide operator that we saw earlier.

The int function can also convert a string to an integer. The simplest use is like this:

a = int("123") # converts string "123" to integer 123

b = int(" 123 \n") # whitespace is ignored, so this is valid and gives 123

c = int("123.0") # throws a ValueError if the string is not an integer

int can handle other bases:

a = int("1001", 2) # 1001 in base 2 (binary) gives 9

b = int("17", 8) # 17 in base 8 (octal) gives 15

c = int("FF", 16) # FF in base 16 (hexadecimal) gives 255

c = int("11", 36) # All bases up to 36 are supported. 11 in base 36 gives 37

In the hexadecimal case, int ignores the case of the letters. So FF, ff, or even Ff will return 255.

Bitwise boolean operations

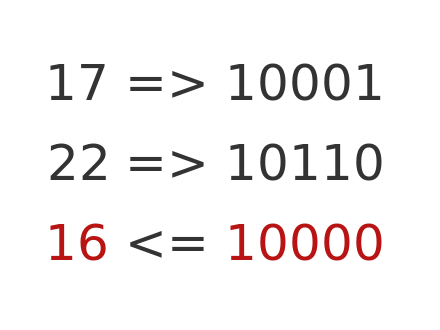

As we saw, an integer can be expressed in binary (base 2) form, for example:

- 17 base 10 is equal to 10001 in binary

- 22 base 10 is equal to 10110 in binary

Python allows us to perform a bitwise AND operation like this:

a = 17 # 10001 in binary

b = 22 # 10110 in binary

a & b # & performs bitwise AND, 10000 binary = 16 decimal

How does this work? A bitwise AND operates on the binary value of the number. It looks at each pair of digits in turn, and gives a 1 if both digits are 1, or 0 otherwise. Here is a diagram that shows the two inputs and the result (in red). The values are shown in decimal and in binary:

Looking at the binary values, the first digits of the two numbers are both 1, so the first digit of the result is 1. The second digits of the two numbers are both 0, so the second digit of the result is 0. For the third and fourth digits, only the first number has a 1 in that position, so the result value is 0. For the last digit, only the second number has a 1 in that position, so the result is 0.

So, each binary digit in the result is 1 if both the equivalent binary digits in input values are 1. It is zero otherwise.

This gives a result of 10000 binary, which is 16 decimal.

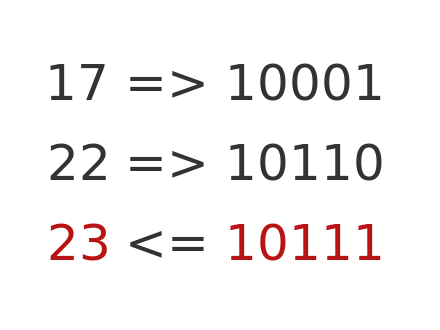

The OR case works similarly:

a = 17 # 10001 in binary

b = 22 # 10110 in binary

a | b # & performs bitwise OR, 10111 binary = 23 decimal

Here is the calculation:

This time, each digit of the output is set to 1 if at least one of the input digits is set to 1. This gives a result of 10111 binary, or 23 decimal.

Python interning

Python uses a technique called interning to improve efficiency. This is completely automatic and is not something you should normally have to worry about. However, it is worth knowing about, as it is a source of commonly quoted bad advice on the internet.

All Python values are stored as objects in memory. This includes integers, so 1, 2, 3, etc, are each stored as a separate object in memory. However, integers are immutable objects in Python, so once we have created an integer object with the value 1, we never really need to create another integer with the same value.

Python uses this fact to perform a small optimisation. When Python starts up, it automatically pre-loads a set of integer objects for every value from -5 to +256. So whenever Python needs to use any of those numbers, it doesn't have to create a new object, it can simply use the one it already has. That makes Python run (slightly) faster. It is applied to integers from -5 to 256 because they are the values that tend to be used most often.

Now, you don't normally have to worry about this, it is just something Python does in the background. But it does have one small effect:

a = 1

b = 1

a == b # True a and b are equal in value

a is b # True, a nd b are the same object

a and b are both set to 1. This means that they are equal. But, due to interning, there is only one integer object with the value 1, so a and b actually reference the same object. So a is b is also true. That would not be the case without interning, because a and b woud then reference two different integer objects that both happened to have value 1. So they would be equal but NOT the same object.

That is all ok. The code behaves as you would expect, with a slightly odd feature that is fully explained by interning. But here is the bad advice. Some people will tell you that, if you want to check if a is equal to 1, you should do it like this:

if a is 1: # Don't do this!!!

do_something

The justification for this is that an is check is a tiny bit faster than an == check. The problem is that interning is not a feature of the Python language, it is a feature of the CPython implementation of Python. CPython is the most commonly used Python interpreter, but it isn't the only one. You should not write code that relies on the idiosyncrasies of one Python implementation. If, for some reason, your code ever ran on a different Python interpreter, it might exhibit very serious bugs.

A tiny speedup is just not worth the danger of littering your code with non-standard Python code.

Related articles

Join the GraphicMaths/PythonInformer Newsletter

Sign up using this form to receive an email when new content is added to the graphpicmaths or pythoninformer websites:

Popular tags

2d arrays abstract data type and angle animation arc array arrays bar chart bar style behavioural pattern bezier curve built-in function callable object chain circle classes close closure cmyk colour combinations comparison operator context context manager conversion count creational pattern data science data types decorator design pattern device space dictionary drawing duck typing efficiency ellipse else encryption enumerate fill filter for loop formula function function composition function plot functools game development generativepy tutorial generator geometry gif global variable greyscale higher order function hsl html image image processing imagesurface immutable object in operator index inner function input installing integer iter iterable iterator itertools join l system lambda function latex len lerp line line plot line style linear gradient linspace list list comprehension logical operator lru_cache magic method mandelbrot mandelbrot set map marker style matplotlib monad mutability named parameter numeric python numpy object open operator optimisation optional parameter or pandas path pattern permutations pie chart pil pillow polygon pong positional parameter print product programming paradigms programming techniques pure function python standard library range recipes rectangle recursion regular polygon repeat rgb rotation roundrect scaling scatter plot scipy sector segment sequence setup shape singleton slicing sound spirograph sprite square str stream string stroke structural pattern symmetric encryption template tex text tinkerbell fractal transform translation transparency triangle truthy value tuple turtle unpacking user space vectorisation webserver website while loop zip zip_longest